| B A R E L Y B A D W E B S I T E |

|

Hizzoner |

|

I'm not sure Hizzoner, seeking to be re-elected mayor of Kansas City, Kansas, really intended to refer to anything gooey, but that's how I read this sign. |

|

In 1994 Hizzoner Joe Steineger and his top assistant, Peter Adams, were tried in U.S. federal court for accepting a $4,000 bribe allegedly paid by a local strip-club operator named P.J. McGraw. Mr. McGraw was the principal prosecution witness, and his handler was Jeff Lanza, an FBI agent. Except for the voir dire, I attended almost every moment of the trial. I rode my motorcycle to the courthouse every day and, because it was summer and hot, I wore shorts, which kind of set me apart. One time a few weeks into the trial I came in in the middle of a session and the judge -- G. Thomas Van Bebber, now chief district judge for Kansas, presiding over what was arguably the biggest trial of his life and certainly one of the biggest trials in Wyandotte County history -- joked, "Let's wait a moment while our friend with the motorcycle helmet gets seated." I always sat in more or less the same place throughout the weeks-long trial, which turned out to be where some of the local print and TV reporters sat, and on the morning the verdict was to be read one of them said to all of us, including me, "Well, where shall we all meet tomorrow morning?" Another time, as people were returning after the lunch recess, I was chatting with a small group about the trial and happened to say, "I'm not sure how much I'd want P.J. McGraw for a friend." One of the women in the group, who'd been sitting behind me for weeks, responded, "He's not so bad." I asked, "Do you know him personally?" "Yes," she said, "I'm his daughter." Even the courthouse was interesting. Newly constructed U.S. federal courthouses are, in my opinion, excessively lavish, and this one is a good example. The hallways are perhaps twice as wide as they need to be. The architectural and decorating details, while making for a deeply impressive building inside and out, must have cost many hundreds of thousands of dollars. Sometimes when the trial got boring I'd try to count up in my head how much money was spent on the unnecessary appointments and fancy architecture in that one room alone, and I was continually amazed. All this in a city and a county that are among the most blighted and crime-ridden in the state. The judge at the Mayor's trial used a wheelchair, and in his courtroom was a really cool lifting device. The judge would roll into the room from a side door straight onto a platform and push a button, and the platform would silently lift him up onto his raised bench, where he'd roll off the platform and then onto his deskal region. Because everyone else must stand when the judge is not, er, seated, watching him machinely mount and descend from the bench on his "deskalator" became a riveting ritual for me, and, I'm sure, for many of the others in the courtroom. This courtroom also had an electronic device I'd never seen or heard of elsewhere. You know how in movies and television, at a sidebar the judge will casually place his hand in front of the microphone he uses? Like that's going to prevent it from picking up the conversation, right? I mean, I'm sure in real life if a judge really does use a microphone, someone's going to have figured out that maybe it's a good idea to show him how to turn it off and on. Anyway, in this courtroom the judge did have an on-off switch, but it wasn't connected to a microphone. Whenever he hit the ON switch, which was during maybe half of the many dozens of sidebars, a stereo amplifier fed loud pink noise into special speakers suspended from the ceiling aimed directly and only at the jury. From my seat on the other side of the courtroom it always sounded like the jury was being rained on. The prosecution, led by Randy Rathbun, a guy who has since been promoted, put on a powerful case, if you believed P.J. McGraw. The defense took its shots in cross, and many of them hit home. Sometimes a whole day would be spent setting up something to come, with no one except the principals knowing what it was, which made that evidence both baffling and difficult to remember. For the defense's side, the Mayor's assistant did take the stand, and he credibly cast doubt on their guilt, but in cross the People cast some doubt on him. And then Joe himself took the stand. (I can call him that because he knew my dad and also because for three decades now he's been farming some land I co-own, which means I talk to him every so often about that. See below.) He did even better on the stand than his co-defendant, proving at least in part why he was elected so often. He was huggly. Even when discussing the nitty-gritty of the politics of being mayor of a medium-sized city not known for its clean government, he sounded like he was your favorite uncle. And he sounded innocent. Which, according to the verdict, he was. His subsequent run for another term as mayor was not so successful, perhaps because of the gooey taint of that trial. Maybe the feds got what they wanted after all. |

|

|

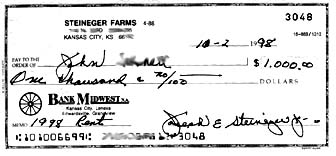

The land Hizzoner was farming was sold on November 2, 1998, so this is the last check from him. He sent along a note congratulating us for finally selling the land and expressing the sentiment that my dad, who bought it over thirty years before, would be pleased with the sale. Joe even stood up from the gallery at a difficult city council meeting and spoke in favor of the zoning we needed, even though he knew it would mean the loss of his farm. Former mayors get listened to, and the zoning change was passed. Joe has class. |

|

|

|

|

|

|