VIII. Theme Answers

The New York Times crossword puzzle always contains

a theme of some sort in the Monday through Wednesday editions, almost always

on Thursdays, rarely on Fridays, and almost never on Saturdays. The larger

(21 by 21 versus 15 by 15) Sunday

puzzle has not only a theme but a title that will always suggest that

theme. You should always pay attention to the theme. In fact, you can't

really say you've solved the puzzle till you've identified the theme or decided there

isn't one. The rest of this page consists of examples of themes.

(In addition, there are a few examples of tours de force sprinkled

in, just so you can see how hard some constructors try. It's these puzzles that you

more casual solvers should admire more.)

The theme

is George Washington, and the theme answers are CHERRY (cherry tree), WOODEN (wooden

teeth), DELAWARE (Delaware River), VIRGINIA (home state), FATHER (of our country), and

DOLLEY (Madison, his seamstress). The theme

is George Washington, and the theme answers are CHERRY (cherry tree), WOODEN (wooden

teeth), DELAWARE (Delaware River), VIRGINIA (home state), FATHER (of our country), and

DOLLEY (Madison, his seamstress).

Some theme

answers are quips and quotations. The quips can be made up by the author of the puzzle or

they can be quotes from well-known people, and they purport to be amusing or

insightful. The various chunks of the answer snake through the puzzle, sometimes in

diagonally symmetrical blocks and sometimes not, sometimes only in the Across answers and

sometimes not. Some theme

answers are quips and quotations. The quips can be made up by the author of the puzzle or

they can be quotes from well-known people, and they purport to be amusing or

insightful. The various chunks of the answer snake through the puzzle, sometimes in

diagonally symmetrical blocks and sometimes not, sometimes only in the Across answers and

sometimes not.

Such quips and quotations usually make the puzzle more difficult to

play, because you get only the one clue for what can be several dozen answer cells. The

first clue will read something like "First part of quip," the next clues will read "Quip:

Continued," and the last clue will read "Last part of quip."

Here's an answer from a Sunday puzzle: "If I had a

nickel for every time I put a dollar in the bank I'd have 1/20 what I have now."

Now, to be honest with you, I don't really get what this particular

one means, but the point is that you are given only one clue for what turns out to be, in

this case, five separate answers occupying 68 cells. (And yes, the author did

require the player to figure out that two of the answers used the numeral 1, that two of

the answers used the SLASH,

that two of the answers used the numeral 2, and that two of the answers used the numeral

0.)

Arguably the best

and certainly one of the most controversial NYT crossword puzzles appeared on Tuesday, November 5th, 1996, which was the day of the last U.S.

presidential election that was not decided by the Supreme Court. This puzzle is so special it requires you to take a detour to learn more about it.

Then come back here. Arguably the best

and certainly one of the most controversial NYT crossword puzzles appeared on Tuesday, November 5th, 1996, which was the day of the last U.S.

presidential election that was not decided by the Supreme Court. This puzzle is so special it requires you to take a detour to learn more about it.

Then come back here.

The theme

of Isabel Walcott's NYT masterpiece of May 10, 1997, was so devious that the

puzzle needed a special notation: "The answer to 53-Across contains a hint to

entering the answers to 20-, 23-, 38-, 48-, and 53-Across itself." The theme

of Isabel Walcott's NYT masterpiece of May 10, 1997, was so devious that the

puzzle needed a special notation: "The answer to 53-Across contains a hint to

entering the answers to 20-, 23-, 38-, 48-, and 53-Across itself."

Here's all you need to figure it out. (Don't scroll down just

yet. Look at the answers for a sec.)

| 20-Across Heavy-duty kitchen implement |

CHERKNE |

| 23-Across 60's sitcom that had a whistled

intro, with "The" |

YGRFITHSHOW |

| 38-Across What a "choosy mother"

might pack for lunch |

JPEANUTTERSWICH |

| 48-Across Unsavory MTV cartoon duo |

BEAVISTHEAD |

| 53-Across Familiar five-word phrase that

means "Excuses are unacceptable!" |

NOSSORS |

Give up? OK, here's the deal. The theme, as stated at

53-Across, is the phrase "No ifs ands or buts."

20-Across BUTCHERKNIFE

23-Across ANDYGRIFFITHSHOW

38-Across JIFPEANUTBUTTERSANDWICH

48-Across BEAVISANDBUTTHEAD

53-Across NOIFSANDSORBUTS

Note also that the three answers that include exactly two of the

three special words spread them out with perfect symmetry, two of each.

This is one of the cleverest themes I can remember.

The theme clues and answers of the September

9, 1997, NYT puzzle by Matt Gaffney consisted of the following: The theme clues and answers of the September

9, 1997, NYT puzzle by Matt Gaffney consisted of the following:

| 17-Across What's the point of annoying

Leno's sheep? |

WHYTEASEJAYSEWE |

| 20-Across 60-Across, in other words |

LOOBGG |

| 38-Across Singers Starr and Kiki look at

each other |

KAYSEYESSEEDEES |

| 52-Across 38-Across, in other words |

KKIICDD |

| 56-Across 17-Across, in other words |

YTTJJU |

| 60-Across Fashion magazine is indebted to a

pop group |

ELLEOWESBEEGEES |

Get it? If you don't, take a moment to look it over for a while

to see what the theme might be, because it's both good and better.

Even if you figured out that every answer consists of the sounds

of the names of the individual letters (e.g., the sound of the letter B is

"bee," the sound of the letter F is "eff," and so on), this puzzle is better

than that. Each answer is rendered twice, once in plain English and

again using only letters.

This is brilliant primarily because of the intricate cleverness of the

clues and answers but also because the constructor managed to fit them into

the many strictures of a crossword grid.

The puzzle

of January 22, 1998, by Patrick Jordan contained these four theme clues and answers: The puzzle

of January 22, 1998, by Patrick Jordan contained these four theme clues and answers:

| 17-Across |

FULFILLAREQUEST |

| 25-Across |

CROSSARIVER |

| 42-Across |

POKEAHOLEIN |

| 53-Across Three of these could complete the

missing clues above |

PRESIDENTSNAMES |

In case you don't want to think as hard as I did, I'll tell you the

missing clues should be Grant, Ford and Pierce.

Emily Cox

and Henry Rathvon used a cute theme in the puzzle of March 22, 1998. Emily Cox

and Henry Rathvon used a cute theme in the puzzle of March 22, 1998.

| Director Martin Scorcese's anagrammatic claim |

ISTRESSROMANCE |

| Jockey Eddie Arcaro's anagrammatic motto |

DORIDEARACE |

| Ulysses S. Grant's anagrammatic advice regarding hangovers |

TRYSUNGLASSES |

| Artist Piet Mondrian's anagrammatic epigram |

IPAINTMODERN |

| Kevin Costner's anagrammatic lament about his videos |

NEVERINSTOCK |

| Carmen Miranda's anagrammatic ballroom tip |

DANCEARMINARM |

| Len Deighton's anagrammatic avowal on writing |

IDOLENGTHEN |

| Poet Denise Leverton's anagrammatic urging |

DELVEINTOVERSE |

Here are

the theme clues and answers to the puzzle of February 3, 2000, by Thomas W. Schier. Here are

the theme clues and answers to the puzzle of February 3, 2000, by Thomas W. Schier.

| 1960's sci-fi series |

SPLOSTACE |

| Arrives ahead of schedule |

EGETSARLY |

| Example |

POCASEINT |

| Start, as a chain of events |

MOTSETION |

| Jack Benny's theme song |

BLOLOVEOM |

| Write or call |

TOUCKEEPH |

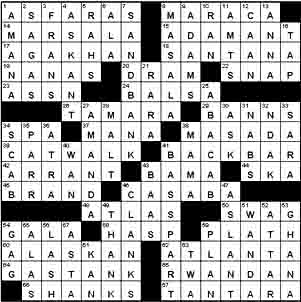

Here's an

extra good example of a theme, by Manny Nosowsky. Manny can be counted on to

deliver at least 6.66% more than expected. This ran on September 6, 1999, a mere Monday, which

means the clues and answers were particularly easy. Here's an

extra good example of a theme, by Manny Nosowsky. Manny can be counted on to

deliver at least 6.66% more than expected. This ran on September 6, 1999, a mere Monday, which

means the clues and answers were particularly easy.

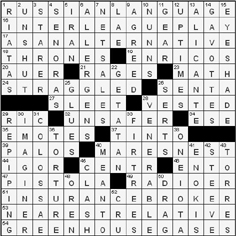

Copyright 1999 New York Times

|

In the third row is FIRST ROUND.

In the fourth row is FIRST BASE. In the

eight row is SECOND RATE.

In the ninth row is SECOND DOWN.

In the thirteenth row is THIRD RAIL.

In the fourteenth row is THIRD PRIZE.

Imagine how difficult it would be to try to get all of those

crossing answers to work, and to keep it symmetrical.

Now consider how much more difficult it would be if you'd

created a grid that required that every single one of the 39 DOWN answers in the

entire puzzle intersect with at least one of your ACROSS theme answers.

But that's not all.

The constructor not only managed to work out all the answers

above but also worked them into a perfectly appropriate full-length Down answer at 6-Down:

FIRST SECOND THIRD.

Finally, this is quite a rare puzzle even if only for the reason that it is not

square.

The width is the usual 15 cells, but the height is 16. |

Here's

another one that violates the 15 X 15 rule. The grid below, published

on January 5, 2006, and written by Vic Fleming, does so for a special reason. Here's

another one that violates the 15 X 15 rule. The grid below, published

on January 5, 2006, and written by Vic Fleming, does so for a special reason.

Copyright 2006 New York Times |

Examine the two Across answers at the

upper left and lower right, then the three theme answers at the

fourth, eighth and twelfth rows. |

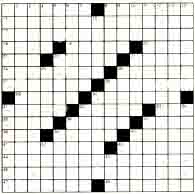

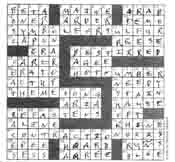

Here's

another one by Manny Nosowsky, from the NYT puzzle of January 7, 2000, a

Friday. The low quality of this scan is all you need to see what makes this grid

special. Here's

another one by Manny Nosowsky, from the NYT puzzle of January 7, 2000, a

Friday. The low quality of this scan is all you need to see what makes this grid

special.

Copyright 2000 New York Times

|

It has two pairs of contiguous 15-letter answers

as well as two other 15-letter answers crossing those first four. As I explain

elsewhere, for a constructor to take on any such grid is a challenge. But that's not

what's special about this one. If you're a

novice cruciverbalist you might not see it, but I assure you all experienced players

recognized as soon as they saw it that this is an especially dense grid. Of

the total of 225 cells, only 21 are black, and that's special.

To use up more than 90% of the cells is so difficult, because

it means so many of your answers must be so long. Long words are, if you think about

it, always more difficult to place in a grid.

If you think about it further you'll see that the fewer black

cells there are, the lower will be the number of clues (what the constructors refer to as

"word-count"). A low word-count (this one has only 66 clues) is an

indication of a puzzle that was difficult to construct and will probably be difficult to

play. Yay. |

Barely

a year after Manny's 21-black grid (above) appeared, it got beat by a bit. Barely

a year after Manny's 21-black grid (above) appeared, it got beat by a bit.

Copyright 2001 New York Times

|

Joe DiPietro constructed

a grid with only 20 black squares. It ran in The New York Times of January

19, 2001. So, all the

praise I expressed above about Manny's grid goes 4.8% more for Joe's.

Surely 19 is next. |

It took over four years, but the record re-belongs to Manny.

It took over four years, but the record re-belongs to Manny.

Copyright 2005 New York Times |

This grid, which ran in the March 11, 2005,

NYT, contains only 19

black squares and only 62 answers.

It also features two triple-stacks of 15 letters each. Who knows when we'll see one with 18? |

It took three and a half years, but the bar has been raised,

er, lowered again.

It took three and a half years, but the bar has been raised,

er, lowered again.

Copyright 2008 New York Times |

This grid in the August 22,

2008, edition of the NYT by Kevin G. Der has taken the record

away from Manny again. It has only 18 black

squares.

As with Nosowsky's example immediately above, there are

two triple stacks. |

Four double stacks.

Four double stacks.

Copyright 2010 New York Times |

The grid at left, by Joe Krozel

(NYT of August 7, 2010), ties the record set two

years before. It too has only 18 black

squares. This is accomplished

by placing two 15-letter answers one on top of the other

at the top and two more at the bottom and two more down

the left side and two more down the right side.

This grid is also quite unusual in that it is

asymmetrical, at least in the typical sense of that term

when referring to crossword grids, which is that the

grid should be the same when it is rotated 180 degrees.

Look only at the three diagonals in the field and you'll

see not one but two asymmetries.

Actually, this grid is symmetrical in a different sense.

If you rotate it forty-five degrees clockwise it is symmetrical

on its new vertical axis, i.e., it displays left-right

symmetry. To see what I mean, cock

your head 45 degrees counterclockwise, then mentally

draw a line from the top of the resulting diamond to the

bottom. If you then fold on that line, the right

half will match the left. (For a deeper discussion

of this topic, go here

in case you haven't already.) For a

grid to have a record-tying number of blacks and

be asymmetrical makes this a true standout. |

Speaking of records, here's one that astonishes crossword constructors, by Frank Longo. It ran

on January 21, 2005.

Speaking of records, here's one that astonishes crossword constructors, by Frank Longo. It ran

on January 21, 2005.

Copyright 2005 New York Times |

This grid contains only 52 answers, which is a record for NYT

puzzles. Frank Longo is known for extraordinary puzzles, and this is certainly one.

You can read how he built this puzzle

HERE. |

Here's

another tour de force, this time by slicing three triple stacks. Here's

another tour de force, this time by slicing three triple stacks.

Copyright 2000 New York Times

If you have Across

Lite installed you can play this puzzle from HERE.

Choose "Ten Grain."

|

This is the grid of the NYT crossword

on June 30th, 2000, constructed by Martin Ashwood-Smith. It

is most extraordinary. Take a look at it for a while, then read on.

As you can see if you look close, there are three contiguous 15-letter answers at the top, one

on top of another. (That right there is tough.)

To match that there are, of course, three contiguous

15-letter answers at the bottom, one on top of another. (So, even tougher.)

But there are also three contiguous 15-letter answers in the middle,

one on top of the other.

Do you care to write the Down clues that fit such a grid?

Now, take another look and you'll see why this grid is not

just extraordinary but, as I say, most extraordinary.

Running right down the middle is yet another 15-letter

answer.

That's a remarkable ten full-length answers, consisting of 141 different cells. Given that

there are a total of 195 answer cells, those ten answers alone constitute over 72% of the entire puzzle! |

This grid is most unusual, possibly unique. Do you see

why?

This grid is most unusual, possibly unique. Do you see

why?

Copyright 2005 New York Times

|

There are only so many ways to

construct a grid that follows the rules of a NYT

puzzle and still have no black squares touching any

others, even diagonally.

Patrick Merrell did it in this December 2, 2005,

edition. The three pertinent rules are (1) that all

answers be three characters or longer, (2) that every

white square appear in both an Across and a Down answer,

and (3) that the grid be 180 degrees symmetrical. |

On July 28, 2007, an astonishing crossword puzzle

named "Special Delivery" was published by Patrick Merrell at his

blog.

On July 28, 2007, an astonishing crossword puzzle

named "Special Delivery" was published by Patrick Merrell at his

blog.

The nature of this puzzle is such that it cannot be published as a

regular crossword in the space available in regular newspapers, which is too bad, because it

exemplifies the fierce nature of crossword constructors to bring us more, to

do better, to get wild. I declare this is the finest example of a

fill-in-the-blank puzzle ever written since November 19, 1863. Below

is the crossword grid. As you can see, it is a bit different.

First, you should go to Patrick Merrell's blog

HERE

and find and download the "Special Delivery" puzzle, then print it out and

play it. Even if you're a complete novice to crosswords, just keep

banging away till you figure out the deal, at which point you'll realize you

won't be needing the answer grid.

Update of March 10, 2011: You can now also go to Merrell's blog about

this puzzle

HERE.

Those of you familiar with acrostics might figure out the deal a bit earlier.

This is the quintessential melding of a crossword and an acrostic,

perfectly executed. Second, read the author's

explanation from his blog of how he created the puzzle.

July 30, 2007 -- A few notes about the construction of "Special Delivery."

The concept: fill a crossword grid using each and every letter from a

selected quote—an anagram of the quote, in effect.

The quote I chose had 143 letters, so I used a 13 square x 13 square grid

(169 total squares) and symmetrically placed 26 black squares in it to

arrive at the necessary 143 white squares.

After symmetrically positioning three themed answers in the grid, I set

about filling the rest of the grid. A list of individual letter totals

from the quote was constantly checked.

A small supply of S's and L's was a bit of a problem. After putting in

the three themed entries, only three S's and two L's were left to use.

There was a fair amount of starting over and backtracking as I learned how

to best manage the list of letters. The one trade-off in making the

puzzle was a larger number of "crosswordy" answers than I'd normally use.

In case you're curious, the last entry to go in the puzzle was 56-Down,

which is also the most obscure answer in the puzzle . . . unless you happen

to be into molecular genetics. (The crossing answers and quote leave

no doubt as to the correct answer, however.) Third, now that you've played this puzzle -- you have, haven't

you? -- try to imagine how

difficult it must have been to construct. Once he chose a quote, the

author had only those exact 143 letters to work into the answer grid.

He couldn't trade a useless Q for a handy L or swap a K for an S. He had that exact

list of letters, and somehow they had to be fit into a crossword grid.

At first it would seem easy, with all those letters to choose from for the

first several answers, but in

pretty short order you're going to run out of the letters you want. A

few answers later

you're going to realize that you've got a bunch of unpopular letters you

absolutely have to cram

into place in place of the letters you really want to use. It's tough enough

to create a half-decent crossword when you have all the letters of the alphabet

available for use anywhere, but for a constructor to be able to create a

rules-compliant 13 X 13 crossword that uses only a fixed set of 143 letters is

so difficult that I wonder whether it has ever been done before. But it's

even harder than that, because 27 of those letters were used up by the three

symmetrically placed theme answers, including one that's a

full 13 letters in length. The way it is all so gently forced to fit

together continues to gast my flabber, and it should yours too. The author of "Special Delivery" joins the the author of

the Election Day crossword in my personal pantheon of

crossword puzzledom, which now

consists of two.  Here are two similar ones from Manny Nosowsky.

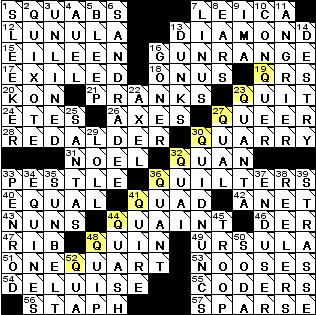

In the February 16, 1996, puzzle immediately below the theme is simply the

letter "Q." Getting this to work with even a commonly used letter such as

"E" or "S" would be tough enough, but getting it to work with such an

uncommonly used letter as "Q" is remarkable, especially considering that most

"Q's" have to be followed by a "U." Notice how the

grid is designed with a nine-cell diagonal of darks so the Qs can always

start the answers. Again, I recommend you try

writing such a puzzle if you want to appreciate what an accomplishment this particular one

was.

Here are two similar ones from Manny Nosowsky.

In the February 16, 1996, puzzle immediately below the theme is simply the

letter "Q." Getting this to work with even a commonly used letter such as

"E" or "S" would be tough enough, but getting it to work with such an

uncommonly used letter as "Q" is remarkable, especially considering that most

"Q's" have to be followed by a "U." Notice how the

grid is designed with a nine-cell diagonal of darks so the Qs can always

start the answers. Again, I recommend you try

writing such a puzzle if you want to appreciate what an accomplishment this particular one

was.

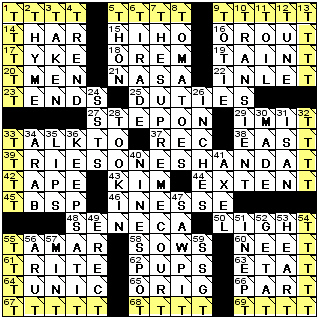

Copyright NYT 1996  In that same vein, Dr. Nosowsky gave us a superb effort in the April Fool's Day NYT of

2000. Here are the twelve theme clues and, as you'll see, the order

doesn't matter.

In that same vein, Dr. Nosowsky gave us a superb effort in the April Fool's Day NYT of

2000. Here are the twelve theme clues and, as you'll see, the order

doesn't matter.

Torment; Some socials; Golfers' needs; Musical notes; Rib;

Sri Lankan exports; Flirt; Informal tops; Plumbing joints; Angers, with "off";

Certain crosses; Timeout signs.

Don't scroll down till you've looked at

the clues to figure out the Theme.

Copyright NYT 2000

It is extraordinary that such a puzzle could be constructed.

Forty-four answers in the grid above start or end with the letter "T."

When you add in the 12 answers that form the perimeter, that's an

astonishing total of 56 theme answers out of a total of 74.

Assuming charitably that the typical puzzle contains as many as four

theme answers and that the average number of answers is as few as 68, that

means this grid contains twelve times more theme answers than

average, which I think might be some kind of record.

As you can imagine, if you can catch on to this theme early, you can

fill in a lot of cells without even looking at the clues. In this

particular case, if you identify the theme after the first two clues, you

can proceed to fill in another 40 letters, which I think also might be

some kind of record.

Identifying the theme in a themed puzzle is satisfying and usually

helpful. The sooner you can do it the better, because once you've identified the

theme you've got a major leg up on figuring out the other theme answers. If before

you even look at the clues you can identify the theme answers' strings of cells in the

empty grid -- and you usually can because they're almost always the longest ones and they're almost always symmetrically placed -- you should strive to

answer the clues that intersect one or two of them.

The November 13,

2000, puzzle in the New York Times by Peter Gordon had a cute theme.

The November 13,

2000, puzzle in the New York Times by Peter Gordon had a cute theme.

| 20-Across One who looks up when someone

yells "duck!"? |

BIRDWATCHER* |

| 38-Across Famous 52-Across |

REVERENDSPOONER |

| 52-Across 20-Across, to 38-Across |

WORDBOTCHER |

*I do have a complaint or two about how the first clue was

punctuated. First, I think there should have been a comma after "yells." Second, I think "duck" should have been capitalized. And I also

figure if someone is yelling a word, it doesn't need an exclamation point.

Specialty

theme. Approximately every several weeks or so the theme will be really

unusual, sometimes visually striking, and I look forward to these the most. Specialty

theme. Approximately every several weeks or so the theme will be really

unusual, sometimes visually striking, and I look forward to these the most.

Rebus crossword. For example,

it might be that several individual cells are to be filled in with your best rendering of

an eyeball, which represents the letters E-Y-E, and all those answers will contain those

letters, such as GREYEST, CHEYENNE, and MONKEYED, which would show up in the answer grid

as GR¤ST, CH¤NNE, and MONK¤D. This is called a rebus puzzle, and

the sooner you catch on to this rarely used convention the easier the puzzle will go.

Here's a good example of a visually striking specialty theme, by Bill Zais and Nancy Salomon, from the

December 1, 1999, New York Times.

Copyright 1999 New York Times

|

In the third row down from the top you'll see

the answer to "Booty location," which is SPANISH MAIN. Centered in the middle row of the puzzle is the answer to "X

marks it," which is THE SPOT.

In the third row up from the bottom you'll see the answer to

"What this puzzle is," which is TREASURE MAP.

So far so good, but nothing special, right?

But wait, that's not all. There are two 15-character diagonal

clues, and you can see the answers are DIAMONDS AND GOLD and EMERALDS AND JADE.

And, of course that's what makes this puzzle not just a

treasure but a treasure map, because X marks the spot. Amazing. |

Copyright 2002 New York Times

|

Here's another one using the same theme in a different way, from Patrick Merrell in the November 7, 2002,

puzzle.

There are eight clues -- not just symmetrically placed but centered as well -- all relating to the theme

of pirates searching for treasure where X marks the spot, and if you squint your eyes you'll see the X.

Update of January 2003: It took till now for someone to point out the obvious to oblivious me

(thanks to the CRU at the NYT Crossword Forum) that there's

yet another theme feature to this puzzle. The centermost four letters are

N

W E

S

If I missed this, how many other tidbits am I missing? How many are you? |

Elizabeth C. Gorski invariably entertains, and her Sunday, August 17, 2003, puzzle is a fine example. The title is "All Keyed

Up," and the theme is a telephone keypad. Below are the twelve relevant answers in context.

Elizabeth C. Gorski invariably entertains, and her Sunday, August 17, 2003, puzzle is a fine example. The title is "All Keyed

Up," and the theme is a telephone keypad. Below are the twelve relevant answers in context.

B

A

I L

N N L

INT1 PAGE2

LINE3

E

D H N

I 0

PART4 TAKE5

6WEEK

P

M D

C

GAME7 8EENS

9PINS

U A

P D I

M

*DATE 0FEET

#SON

L E S

E D

S

S

Here's another example

of a specialty theme, co-construed by Nancy

Salomon, partnering this time with Harvey Estes, in the NYT of December 16, 1999. Here's another example

of a specialty theme, co-construed by Nancy

Salomon, partnering this time with Harvey Estes, in the NYT of December 16, 1999.

The clue for 3-Down is "Jungle swinger." The clue

for 7-Down is "With 11-Down, 3-Down's last words?"

T S T

A O H

R M E

Z E V

A B I

N O I

T D I

H Y I

E G I

A R I

P E I

E A I

M S I

A E N

N D E

The two

theme answers in this March 16, 2000, NYT by Peter Gordon are SAYCHEESE and

PUTONAHAPPYFACE. The two

theme answers in this March 16, 2000, NYT by Peter Gordon are SAYCHEESE and

PUTONAHAPPYFACE.

So what, right?

But now squint your eyes and take another look at the grid, right. |

© 2000 New York Times

|

You don't need to squint anything to guess which letter starts every single one of the 74 clues in this January 1, 2004, puzzle by

Richard Silvestri.

You don't need to squint anything to guess which letter starts every single one of the 74 clues in this January 1, 2004, puzzle by

Richard Silvestri. |

|

Here the "S" (try squinting again) is made up of the white squares, in a NYT grid from Mark Diehl on

April 10, 2004.

Here the "S" (try squinting again) is made up of the white squares, in a NYT grid from Mark Diehl on

April 10, 2004.The theme is stated at 30-Across, where "Moniker suggested by the pattern of white squares

in this grid" = THE MAN OF STEEL. |

|

See anything unusual about the letters in the grid below?

Forget about any meaning, just scan the letters.

See anything unusual about the letters in the grid below?

Forget about any meaning, just scan the letters.

Yes,

you're right, in this superb effort by Patrick Berry from March 21,

2002, the only vowel is the letter "A." Yes,

you're right, in this superb effort by Patrick Berry from March 21,

2002, the only vowel is the letter "A."

Find another puzzle on the

Internet or anywhere that uses only one vowel.

Also, this puzzle

uses only 16 of the 26 letters of the alphabet, which sets it apart for that reason

alone. |

On Saturday, April Fool's Day, 2006, there ran a NYT

crossword that epitomizes the cleverness constructors are capable

of, in this case two of them, Kevan Choset and David Kwong.

On Saturday, April Fool's Day, 2006, there ran a NYT

crossword that epitomizes the cleverness constructors are capable

of, in this case two of them, Kevan Choset and David Kwong.DO NOT

CLICK the answer grid below till you've taken a good look at it,

especially the corners. Note the three theme clues:

- "What some of the letters in this puzzle

seemingly have" = OPLACETOGO

- "How you have to think to solve this puzzle"

= OUTSIDETHEBOX

- "Spills out, in the Bible" = OVERFLOWET

Now note also certain unlikely answers.

- In the upper left we have "Ltrs. may be

written in them" = TALS.

- In the upper right we have "Row makers" = OES

- In the lower left we have "Precollege" = ELH.

- In the lower right we have "Language from

which shawl and divan come" = FARS.

Without playing the puzzle you probably can't figure out the

theme, and I suspect many who did play it the best they could

couldn't figure it out either and gave up. To understand the

theme, go ahead and click the answer grid now.

|

|

The grid is mildly marred by the fact the upper right and lower left

across answers contain an extra letter, but this is still an

exceptional accomplishment in crossword puzzle construction, and we

aren't likely to see any such thing again soon. |

Here are two more examples of interesting grids, each

forming a pleasant pattern of crosses.

Here are two more examples of interesting grids, each

forming a pleasant pattern of crosses.

© 2002 New York Times

If you think about it you'll realize that by imposing such a grid on himself the constructors made

their jobs a lot more difficult.

We can compare how each handled the task.

The one on the left was done by Patrick Merrell, whose NYT crosswords never fail to excel. It ran in the NYT on August 30, 2002, a Friday. As you can see

(try squinting your eyes), there are five symmetrically placed plus signs as well as two symmetrically placed minus signs. Merrell

took full advantage of this grid by including four special Across theme answers, the two at the very top and the two at the very bottom.

1-Across: "Fringe benefits" = PLUSSES

8-Across: "Cathedral sights" = CROSSES

63-Across: "They may be at the end of the line" = HYPHENS

64-Across: "Bad points" = MINUSES

Lovely.

The one on the right, from six days earlier (a NYT Saturday), is somewhat less inspired, and it has no theme to save it. Although the grid is

pretty compared to most, filling that grid seems to have gotten the better of the constructor. Here the clues and answers are just

a bit less fresh and approachable than is usual for NYT

crosswords, and a few are worthy of comment.

40-Down's clue is "Suez Canal promoter," and the answer is LESSEPS. Not exactly a household name, but not all that

tough to get if you have the proper references.

But the "P" of that 40-Down intersects with a weak and obscure answer. 53-Across's clue is "Surpass," and the answer is

OVERTOP. Now, I admit I don't know whether "overtop" is a verb, but I don't care because I don't plan to use it. Besides, I

think more fun could have been had with the same letters broken up into the two-word answer "OVERT OP." But then, I am

not a crossword constructor.

Along those same lines, with regard to the diagonally opposite corner I have to mention the answer to 1-Across. The clue

is "Takes up the challenge," and the answer is HAS AT IT. But those seven letters could be broken up into words in a more interesting way, for which a clue might be

"Sucks."

The next specialty theme example (also by Patrick Merrell, in the October 24, 2002, NYT puzzle) is intricate, which means it was difficult to

construct, which means it deserves your admiration.

The next specialty theme example (also by Patrick Merrell, in the October 24, 2002, NYT puzzle) is intricate, which means it was difficult to

construct, which means it deserves your admiration.

The theme clue at 20-Across is "What's hidden in this puzzle" and the answer is strung symmetrically throughout the grid:

AMESSAGEIN

THEFIRSTLETTERS

OFTHECLUES

So, what does this mean? It means that if you write the first letter of every one of the clues, in order, starting at 1-Across

and ending at 60-Down, they spell out the following message:

"The good news is you've spotted the hidden message. The bad news is that this is all it has to

say."

Imagine how difficult it would be to get all this just right.

- The theme answer is symmetrical.

- The theme answer is perfectly written, i.e., it is accurate, error-free, on-point, and natural-sounding.

- The initial W at 20-Across is perfectly in keeping with NYT clues of this sort, which means it is perfectly placed. I have to

wonder whether this was fortuitous.

Update of August 20, 2003: The

author says in an e-mail today, "BTW, I wrote the 20-Across clue in the

MESSAGE IN THE CLUES puzzle before the hidden message. The 'W' that the

clue started with was the catalyst for then writing the hidden message."

- The resulting message is perfectly written, i.e., it is entirely idiomatic and grammatical.

- The resulting message, in answer to the question asked at 20-Across, is cute.

Lovelier.

There are less intricate examples of this theme here and here.

The NYT Sunday puzzle that ran on April 13, 2003, by Charles Deber, contains a theme that at first glance might seem

unexceptional.

The NYT Sunday puzzle that ran on April 13, 2003, by Charles Deber, contains a theme that at first glance might seem

unexceptional.

Here are the theme clues and their answers.

| If I have ___ |

SEVENTY TWO DARK SQUARES |

| . . . and I am ___ |

TWENTY ONE BY TWENTY ONE |

| . . . and I am ___ |

MODERATELY CHALLENGING |

| . . . and I have ___ |

ONE HUNDRED FORTY WORDS |

| . . . then I must be ___ |

TODAY'S CROSSWORD PUZZLE |

This is anything but unexceptional. It is jump-up-and-down extraordinary.

First, it does meet, of course, the criteria for the symmetrical placement of theme answers, in this case three full-length

21-character answers and two 20-character answers.

Second, the sentence is natural-sounding, not strained.

Third, and most important, the sentence is true.

Think how hard it must have been to get this sentence to be true, considering the specific numerical facts asserted in the first and

fourth answers.

The first and fifth clues. If you think about it, if there happened to be 73 dark squares instead of 72 as

claimed then the answer to the first clue would have to change to SEVENTYTHREE, which is two characters longer than SEVENTYTWO,

which immediately creates serious grid-layout problems for the constructor.

First, changing from SEVENTYTWO to SEVENTYTHREE means changing four of the Down answers that crossed the original answer, which might

or might not be a big deal.

But second is that correcting the first answer from SEVENTYTWO to SEVENTYTHREE changes the answer! If there really were 73 dark

squares when the answer said SEVENTYTWO, changing the answer to SEVENTYTHREE takes up two more dark squares in the grid, which

immediately changes the correct answer from the aforementioned SEVENTYTHREE to SEVENTYONE, which of course immediately changes the

number of dark squares again, which immediately changes the correct answer again. This becomes a crazy loop, where every

correction in one answer and every grid-change immediately creates a problem somewhere else.

And, if you remember that diagonal symmetry must be maintained, it's 100% worse than all that, because every time the length of the

answer to the first clue changes, the length of the answer to the symmetrically matched clue, the fifth one, must also change

(which, of course, also means the answers to some of the crossing Down answers must also change), which means the correct answer to the

first clue instantly changes yet again.

The fourth and second clues. And while you're looping crazily around all the combinations of the first clue's

answer, you also have to make sure the answer to the fourth clue changes to reflect the current total number of words (answers)

in the puzzle. Of course, any changes in the length of that answer will instantaneously change both the accuracy and the length of

the answer to the first clue, which will instantaneously change the length of the fifth clue as well, of course, which will

instantaneously change the answer to the first clue yet again.

And, of course, if you actualy do change the number of answers from 140 then that changes the length of the answer to the fourth

clue, which immediately changes the length of the answer to the second clue, which, remember, must match the fourth answer

symmetrically. Both of these changes instantly change the answer to the first clue, which instantaneously changes the length of

the fifth clue as well, which then changes the answer to the first clue, which then changes the . . .

And don't forget, every time you change an Across answer you have to change some of the Down answers, which can affect the Across

answers that cross those new Down answers, which can affect the Down answers that cross those new Across answers, which

might well change the answers to the first and fourth clues. (I assume that it is because of the extraordinariness of this puzzle

that the editor allowed the unusual answer at 99-Down, TZAR. If a theme is chosen and executed well enough, we are all the better

for it if a liberty is taken.)

I am the better for having studied this particular puzzle a bit, and I hope you are now too.

The title of the Sunday, December 28, 2003, NYT puzzle was "Headlines that Make You Go 'Huh?'" The constructor

is Seth A. Abel. All of the theme clues begin with "Ambiguous headline about," and here are three

humorous examples:

The title of the Sunday, December 28, 2003, NYT puzzle was "Headlines that Make You Go 'Huh?'" The constructor

is Seth A. Abel. All of the theme clues begin with "Ambiguous headline about," and here are three

humorous examples:

| Ambiguous headline about school cooking lessons |

KIDSMAKETASTYSNACKS |

| Ambiguous headline about the Bush Cabinet |

ONEILLISFEDSECRETARY |

| Ambiguous headline about a police action |

COPSHELPDOGBITEVICTIM |

Another first-rate example of a specialty

theme is the Sunday NYT puzzle whose title was "Vicious Circle." The theme

answers were GEORGEKAUFMAN, FRANKLINDADAMS, ROBERTBENCHLEY, DOROTHYPARKER, ALEXANDER

WOOLCOTT (in two answers), HAROLDROSS, and EDNAFERBER. Another first-rate example of a specialty

theme is the Sunday NYT puzzle whose title was "Vicious Circle." The theme

answers were GEORGEKAUFMAN, FRANKLINDADAMS, ROBERTBENCHLEY, DOROTHYPARKER, ALEXANDER

WOOLCOTT (in two answers), HAROLDROSS, and EDNAFERBER.

And if that's all there was to the theme then it still would

have been fairly impressive to get pairs of those exact people's names to match up in length and to be diagonally symmetrical (and, of course, to be factually

accurate). Realize, once you've chosen an answer such as GEORGE KAUFMAN, you're pretty much stuck with it. You can't just go

around changing letters the way you can with a shorter answer. For example, by changing only one letter the answer BAT can

be changed to CAT, EAT, FAT, GAT, HAT, KAT, LAT, MAT, NAT, OAT, PAT, RAT, SAT, TAT, VAT, WAT, YAT; and BET, BIT, BLT, BOT, BUT; and BAA,

BAD, BAG, BAH, BAM, BAN, BAR, BAS, and BAY. BAT can be changed in a lot of ways in order to accommodate the perpendicular answers,

but you can't just go around changing GEORGE KAUFMAN to GLORGE KAUFMAP and not expect someone to notice.

Anyway, the fun part of this puzzle, the unusual part, is at 54-Across. The clue

reads as follows:

Where the smart set sat [answer to be

entered in the

appropriate manner]

The answer is ATTHEALGONQUINROUNDTABLE, but what's unusual about it

is that that answer appears in a circle (well, OK a square, which is almost a perfectly unround circle). The first part of that

answer reads ATTHEAL, then you have to turn the corner downwards to fill in GONQUI,

then you have to go left to fill in NROUND, and finally you go up with

TABLE to complete the circle.

ATTHEAL

E G

L O

B N

A Q

T U

NROUNDI

James M. and James C. Jenista used a similar idea in a more fiendishly twisted way in the

Saturday, January 3, 2004, NYT.

James M. and James C. Jenista used a similar idea in a more fiendishly twisted way in the

Saturday, January 3, 2004, NYT.

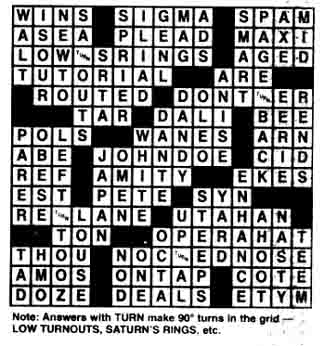

|

You can see four white cells with what looks like a blob that runs from the

northwest corner to the southeast. That blob, if you could read it, says TURN.

Until you get that figured out, if ever, this puzzle makes no sense.

|

For example, the clue at 17-Across is "Disappointing election results," and once you have worked out the Down

answers you're left with the answer LOW_SRINGS. If you make the turn, the answer turns out to be LowTURNouts.

As another example, also in the upper left corner of the grid, 4-Down's clue is "Discovery of Galileo," and the

answer appears to be SA_OUTS. As if you didn't get it already, the answer really is SaTURNsRings. When

was the last time -- whether in the field of crossword construction or any other -- that you came up with an idea this clever?

These rare puzzles -- the ones with a wickedly hidden theme that

requires you to strain your imagination just to figure it out -- are by far the most

enjoyable. I'm sure there's some reason they don't appear any more often than they

do, although as far as I'm concerned it's not much of one. If you decide to take up

the playing of crosswords and you stumble onto one that just

doesn't seem to be making sense, it's probably one where you really have to think outside

the box. Have fun.

|

Click

?

at the top of any page to see all the nifty navigation aids, including

Search Site and Site Map.

Click

?

at the top of any page to see all the nifty navigation aids, including

Search Site and Site Map.

Click

?

at the top of any page to see all the nifty navigation aids, including

Search Site and Site Map.

|